For many of us, Hans Christian Anderson’s The Little Mermaid was our introduction to this fascinating and compelling myth, but stories of mermaids have appeared in every culture. Her form has been the chosen subject of diverse artists like Munch, Waterhouse, Beardsley, Pyle, Rubens and Bosch. Shakespeare mentioned mermaids and sirens repeatedly in his work, while Yeats, Eliot, Wilde, Barry, and Baum welcomed them into their own colorful poems and tales. Who is she, and why are we compelled to seek her out?

Looking Backwards, We See . . .

The earliest references to a half-man/half-fish god point to the Babylonians’ sea-god, Oannes, or Ea, who rose from the Erythrean Sea and taught us our letters. Oannes was called Lord of the Waves and was depicted as an amphibious creature with the torso and head of a man, with his bottom half resembling that of a dolphin. Early images of Oannes show him as a man wrapped in a fish cloak. A civilizing force for the good, and light, and life to his people, he represented the positive values connected with the sea. The Syrians and Philistines worshipped Oannes’ partner as a fishtailed moon goddess overseeing generation and fertility and called her Atargatis or Derceto. Atagartis was an important fertility goddess, representing the darker night forces of love and their potentially destructive power. As Dea Syria, her cult reached as far as Britain. The Hindus recognized a group of beautiful and talented water goddesses called the Apsaras. In Japanese and Chinese legends, there were not only mermaids but also sea-dragons and the dragon-wives. The Japanese mermaid known as Ningyo wards off misfortune and preserves peace in the land; she is depicted as a fish with a human head.

The British Isles also describe merfolk in their tales. The Comish knew mermaids as Merrymaids, the Irish as Merrows or Muirruhgach, and some sources describe them as living on dry land below the sea with enchanted caps that allow them to pass through the water without drowning. Commonly, the women were very beautiful, but the men had red noses, pig-eyes, green hair and teeth, and a penchant for brandy. (No wonder mermaids were always looking to humans for love!) In the Shetlands, the mermaid is called Sea-trow, and they are able to take off the animal skin (usually a seal) that allows them to swim through the water like a fish to walk on land like humans.

The Neck is found in Scandinavia, along with the Havfrue (merman) and the Havmand (mermaid). The Neck, however, was able to live in both salt and freshwater. The Norwegian mermaids known as Havfine were believed to have very unpredictable tempers. Some were known to be kind, others to be incredibly cruel; it was considered unlucky to view one of them.

German mythology has many mermaids. There are the Meerfrau, the Nix and the Nixe who were the male and female fresh-water inhabitants treacherous to men. The Nixe lured men to drown while the Nix could seem like a dwarf or a golden-haired boy (in Iceland and Sweden, they could also take the form of a centaur). The Nix loved music and could lure people to him with his harp; if he were in the form of a horse, he would tempt people to mount him and then dash into the sea to drown them. While he sometimes desired a human soul, he would often demand annual human sacrifices. In the Rhine region, there are the Lorelei. The Germans also knew the Melusine as a double-tailed mermaid. Russian myths. include the daughters of the Water-King who live beneath the sea, the water-nymph that drowns swimmers, known as the Rusalka, and the male water-spirits known as the Vodyany who followed sailors and fishermen.

Greek and Roman myths provide the first literary description of the merfolk as Homer mentions the sirens during the voyage of Odysseus (although he does not provide a physical description). Ovid, on the other hand, writes that the mermaids were born from the burning galleys of the Trojans where the timbers turned into flesh and blood and the “green daughters of the sea.” Although not all ancient water gods or spiritual personifications were Mer people, water nymphs and sirens frequently have been mistaken for merfolk. Clearly, the mythology of the mermaid begins with water deities, but where is she now?

A Transformation Begins

The Greeks transformed Atargatis into Aphrodite, born from the sea and retaining her close connections with it, but fully human in form. Her fish attributes were transferred to her escorts, the Tritons, and, more rarely, the female Tritonids. Aphrodite was also a fertility goddess, her companion the sacred dolphin. Many of the symbols associated with Aphrodite, subsequently the Roman Venus, are retained in the mermaid myth. Her mirror, representing not only her beauty but also her connection with the moon, and her abundant flowing hair, symbolizing an abundant love potential, were both attributes of Venus in her role as fertility goddess. Her comb, necessary to keep all that hair in order, carried sexual connotations for the Greeks, as their words for comb, kteis and pecten, also signified the female vulva. Thus, the mermaid is the surviving aspect of the old goddesses, particularly as the link between passion and destruction.

Knowing this, we can easily see how the Medieval Church used the mermaid/siren symbol to embody the lure of fleshy pleasures shunned by the God-fearing. The mermaid became a victim of the repressive sexual attitudes of the Christian Church, and carvings of her figured prominently in church decorations in the Middle Ages, symbolically reminding worshipers of the fatal temptations of the flesh. By depicting mermaids as dangerous temptresses with no souls of their own, the Church was stating deeply held beliefs about all women as the beautiful, helpful, and powerful mermaid was stripped of all her spiritual qualities. Michelangelo created the ultimate vision of the siren as seductress in the central image of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. In “The Fall of Man and the Expulsion from Paradise,” a mermaid-like creature with a female body from the waist up and a snake or fish body from the waist down is shown seducing Adam and Eve. By the reign of Queen Elizabeth, the mermaid had become a symbol of prostitution.

In her book The Mermaid and the Minotaur, Dinnerstein observes that

“Myth-images of half-human beasts like the mermaid and the Minotaur express an old, fundamental, very slowly clarifying communal insight: that our species’ nature is internally inconsistent, that our continuities with, and our differences from, the earth’s other animals are mysterious and profound; and in these continuities, and these differences, lie both a sense of strangeness on earth and the possible key to a way of feeling at home here.”

Carl Jung suggested that supernatural forces spring from the fusion of two biologically different entities, opposites that embrace and explain practically everything. Jung believed symbols materialize on their own account in our dreams, the expression of which is beyond the dimensions of time and space and in the sphere of unspecified and unlimited. These symbols, therefore, possess a numinous character and impress themselves on the general consciousness, disturbing for those minds used to operating within the limits of logic and rationality. Nevertheless, we can suppose that primordial images, sediments of accumulated memory, and collective input have a life of their own, independent of single individuals. As children, we dream of monsters; what matters is that they approach and threaten, and we are astonished, terrified, bewitched, and petrified, and we either flee or overcome them. Often, the dream repeats repeatedly seeking integration and resolution.

Jung also observed

“A symbol always stands for something more than its obvious and immediate meaning. Symbols, moreover, are natural and spontaneous products. No genius has ever sat down with a pen or brush in hand and invented a symbol. No one can take a more or less rational thought, reached as a logical conclusion or by deliberate intent, and then give it “symbolic form.”

There are many symbols, however, that are not individual but collective in their nature and origin. These are chiefly religious images. The believer assumes that they are of divine origin revealed to us, whereas the skeptic knows they are invented. Both are wrong. It is true, as the skeptic notes, that religious symbols and concepts have been the object of careful and quite conscious elaboration for centuries. It is equally true, as the believer implies that their origin is so obscured by the past that they seem to have no human source. However, they are, in fact, “collective representations emanating from primeval dreams and creative fantasies. As such, these images are involuntary spontaneous manifestations and by no means intentional inventions.” In fact, the mermaid archetype is so widespread among cultures that one may conclude that it must fulfill a particular need in the human collective consciousness. The mermaid is one of the most persistent and pervasive symbols of the old Goddess energy for women, particularly the mysterious, life-generating element.

In much 19th-century creative art and literature, romantic yearnings gave rise to a search for more personal, frequently mystical, themes. As submarine femme fatale, the mermaid became the perfect symbol of the attractions of doomed passion, a favorite theme frequently indulged with a masochistic thrill, as in Burne-Jones’ painting, “The Depths of the Sea” (1887), which endowed its grisly subject with a haunting beauty.

Here, the mermaid (in her guise as a siren) calls men to abandon their Self, to hurl into the deep, to sprout wings, to transform, to die to self, and emerge into a new form with new knowledge and understanding. We cannot overlook the significance of sirens as creatures of water, for water has powerful symbolic value. It can sustain life, give comfort and it is a source of life and abundance. Water is the symbol we use for baptism and spiritual rebirth and renewal. It is the primordial soup; it represents purification and regeneration and is our birth chamber. Water can also be destructive, causing inundation, drowning and death. Bachelard states,

” In point of fact, the leap into the sea, more than any other physical event, awakens echoes of a dangerous and hostile initiation. It is the only, exact, reasonable image, the only image that can be experienced of a leap into the unknown. It is in the sea, the womb, and the grave, all places of birth, rebirth, and regeneration, where the enigma of transformation is concealed. The danger and seduction of the sea becomes a metaphor for the womb, the grave, and the dangers of the feminine realm.”

As such, mermaids are symbols of both death and immortality. They call us to the unknown, to change and transformation, the essential passage from one space to another, from one condition to another. They serve as escorts during times of transit, danger, transformation, uncertainty, sea voyages, and missions of war. They urge us to become something new. Fear of the mermaid is the fear of upsetting the established equilibrium, fear of the unknown, fear of transformation, fear of learning, fear of losing oneself, fear of being out of control, and fear of descending into the deep (the unconscious).

Full fathom five thy father lies;

~William Shakespeare, The Tempest

Of his bones are coral made;

Those are pearls that were his eyes:

Nothing of him that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.

Sea-nymphs hourly ring his knell

Burthen Ding-dong

Hark! now I hear them,–Ding-dong, bell.

And so, in closing, I ask: Where can the Mer people take you? Where will you follow them to?

Sources

- Bachelard, Gaston. Water and Dreams: An Essay on the Imagination of Matter, Pegasus Foundation 1983.

- Brewer, E. Cobham, Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, Cassell Reference, 16th ed. 2001.

- Campbell, Joseph. The Power of Myth, Apostrophe S Productions, Inc. 1988.

- Dinnerstein, Dorothy. The Mermaid and the Minotaur, Harper and Row 1963.

- Farrar, Janet and Stewart. The Witches’ Goddess: The Feminine Principle of Divinity, Phoenix Publishing 1987.

- Jung, Carl. Man and His Symbols, Laurel 1964.

- Lao, Meri. Sirens: Symbols of Seduction, Inner Traditions, 1998.

- Lum, Peter. Fabulous Beasts, Thames and Hudson, 1951.

- Philpotts, Beatrice. Mermaids, Ballantine Books, 1980.

Images

In order of appearance:

- Mermaid. Watercolor, public domain. Found at: https://bumblebutton.blogspot.com/2013/07/free-images-of-mermaids-for-you-to.html. Accessed 5.19.24.

- “Ningyo no zu” woodblock-printed flier dated 1805, public domain. Found at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ningyo#/media/File:Ningyo-no-zu-Bunka02-05.jpg. Accessed 5.19.24.

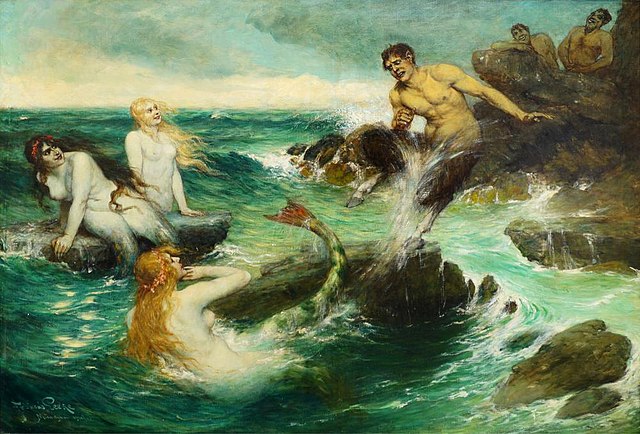

- The Mermaids by Ferdinand Leeke, public domain. Found at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ferdinand_Leeke_-_The_Mermaids,_1921.jpg. Accessed 5.19.24.

- A Mermaid by John William Waterhouse Royal Academy. Found at: https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/work-of-art/a-mermaid. Non-commercial use only.

- A merman, by the sea. Woodcut, public domain. Found at: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/btwswfgu/images?id=jhrxzq5e. Accessed 5.19.24.

- The Depths of the Sea by Edward Burne-Jones, © President and Fellows of Harvard College. Image used under the terms of use for personal, noncommercial use. Found at: https://harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/298102. Accessed 5.19.24.